Sunday, December 6, 2009

Ice storm memories leave bad taste for many

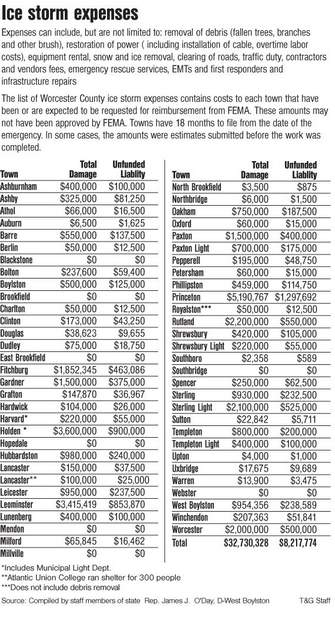

A year later, power options generate steam

Carolynn B. McCarthy a member of the Lunenburg Utility Task Force stands with Carl Strathmeyer of Lunenburg who is holding a Hendrix Spacer Cable a device to help secure power lines in wooded areas. They are helping to develop a plan for a municipal power option in Lunenburg. (ED COLLIER)

By Lisa Eckelbecker TELEGRAM & GAZETTE STAFF

leckelbecker@telegram.com

Nearly one year after a powerful ice storm sealed parts of Central Massachusetts in a treacherous glaze, the state has a new law aimed at forcing investor-owned electric utilities to beef up their emergency procedures and a group of consumers and public officials who want something more — a chance to kick those utilities out. It's a difficult goal to reach. State legislators have filed bills since 2002 aimed at updating the rules cities and towns need to follow to take over the poles and wires within their borders. None has moved forward.

A power line is strung in close proximity to this tree limb along Route 2A in Lunenburg. Thousands of tree limbs fell during last December's ice storm causing power outages throughout the region. (ED COLLIER)

Stanley W. Herriott, manager of the Ashburnham Municipal Light Plant, stands in a warehouse filled with supplies that replenished the stock used during last December's ice storm. (T&G Staff / RICK CINCLAIR)

Extensive cleanup operations were in full swing last December after a devastating ice storm struck the region. Here a crew trims tree limbs resting on utility lines along Route 56 in Rutland. (2008 T&G File Photo / DAN GOULD)

Yet even as electricity providers large and small, municipal and investor-owned, gird for winter under new procedures written after the ice storm, some consumers and public officials critical of Unitil Corp. of Hampton, N.H., and its electric operations in northern Central Massachusetts contend the state's new utility law and the utilities' own changes may not go far enough.

“I think as long as we don't have the choice to be able to form our own municipal companies, all we can try to do is regulate the utility industry,” said Carolynn B. McCarthy, a member of the Lunenburg Utility Task Force. “The regulatory steps that were put in place before the ice storm didn't protect us, and it remains to be proved if the steps the statehouse put in place just recently will be enough to protect us.”

More than 375,000 electric customers in Massachusetts lost power during the storm that began late Dec. 11, 2008. That included more than 100,000 National Grid electricity customers in Worcester County and all of the 28,500 homes and businesses served by Unitil subsidiary Fitchburg Gas & Electric Light Co. in Fitchburg, Lunenburg, Townsend and Ashby. Thousands of customers of municipal utilities lost electricity, too. Some Central Massachusetts consumers did not regain power until Christmas.

Last month, the state Department of Public Utilities said it could not fine Unitil but concluded that Unitil did not plan or train enough for a significant emergency, and that its communications and tree-trimming programs were inadequate. It ordered Unitil to undergo a management audit.

Also last month, Gov. Deval L. Patrick signed into law what was known on Beacon Hill as the “Unitil bill.” Among its measures, it requires investor-owned electric and gas utility companies to annually file emergency response plans with the state and gives the DPU authority to fine utilities and place into receivership those with fewer than 100,000 customers.

“In so many areas of our lives, much of what a company does or doesn't do is driven by confidence. A car company doesn't want to lose the confidence of their customers,” said state Rep. Jennifer E. Benson, D-Lunenburg. “What we have here is companies that can operate regardless of whether they're operating well. Now we're saying, ‘That's not going to happen anymore.' ”

Not everyone is confident that the threat of penalties after an incident is enough to prevent problems. Fitchburg Mayor Lisa Wong stayed up the night before the ice storm reading utility emergency response plans, only to watch as they were not carried out, she said. She favors legislation addressing communities that want to buy out utility companies and form their own municipal utility providers.

“That's like taking the Unitil bill and making that applicable 365 days a year,” Ms. Wong said. “That's probably the biggest incentive I can see for companies.”

Unitil understands that skepticism about the company's possible future performance exists, but company officials have focused over the last year on making changes, said spokesman Wesley B. Eberle.

“I think the company stands more prepared than ever to confront severe weather events like we had last year,” he said.

After the storm, Unitil hired National Grid veteran Richard L. Francazio as its new director of emergency management and compliance, and conducted two company-wide drills in the past year plus “table top” exercises, which are analyses of emergency situations. It also adopted 28 recommended changes to its procedures, covering everything from public communications to the management of repair crews.

Under Mr. Francazio, Unitil restructured its command system during emergencies, added weather services to give the utility five-day forecasts for predictable events, set up a process that guides Unitil workers through a three-day checklist before events and created a way to get the names of customers with critical power needs, such as those on life support, to local emergency workers.

Workers in Unitil's natural gas operations have been trained to help at sites of fallen electrical wires, according to Mr. Francazio, and capacity at the company's call center was expanded.

After the ice storm, customers struggled to get accurate information about repairs. Mr. Francazio said Unitil has devised processes to get information about an event up to a chief information officer, so that updates on outages and repairs can be given to Unitil workers, customers, public officials, the media and others.

Stormy weather last week gave Unitil a chance to try out some of its new procedures. It opened emergency operation centers, Mr. Francazio said, and restored power within minutes to about 100 customers.

“If the event had escalated, we were ready to respond,” he said.

As to Unitil's response to consumers who favor forming municipal utilities, Mr. Eberle said, “We believe than any fair and impartial assessment will show that Unitil, or for that matter any investor-owned utility, is still the best option for communities today.”

Massachusetts is home to 41 municipal electric utility organizations, including several in Central Massachusetts. The munis, as they are known, grappled with the ice storm, too.

Stanley W. Herriott, manager of the Ashburnham Municipal Light Plant, ordered all power to the town's 3,000 customers turned off Dec. 12 because of fears that residents clearing trees would accidentally saw through a live wire. Ashburnham began restoring power the next day and connected the last customer on Dec. 24. That's nearly as long as it took to bring the last Unitil customers back online, although Unitil's response became more robust after National Grid began assisting on Dec. 20.

“We had people come in plenty angry,” Mr. Herriott said. “We gave them the best information we could give them. I was out there every day, talking to people, telling them, ‘Look, you live 1,000 yards off the road, you're going to be one of the last customers we get to.' ”

Proponents of municipal electric companies say they charge less than investor-owned utilities and offer better service. With no investors to reward, proponents say, there's more money to invest in new equipment and technologies.

State law allows communities to form municipal utilities, but the only one to do since 1926 is Devens, which is managed by the Massachusetts Development Finance Agency. The issue, municipal proponents say, is that even if a community proposes to buy a corporation's utility infrastructure, the corporation can effectively block the move by declining to sell.

Proposed legislation would enable a sale once a fair price for utility assets is determined. State Rep. Stephen L. DiNatale, D-Fitchburg, said legislators are working on showing that DPU could determine the value of a company's utility assets.

“We're trying to demonstrate that's something that's achievable,” Mr. DiNatale said. “As far as I'm concerned, the challenge for a city like Fitchburg is finding the resources.”

Ms. McCarthy of the Lunenburg Utility Task Force said the group has crunched numbers and believes a municipal utility covering Lunenburg, Fitchburg, Ashby and Townsend could issue 30-year municipal bonds, acquire Unitil electric assets and provide service at rates 1 percent to 3 percent below Unitil while adding utility employees, including linemen.

“At this point, it's too much speculation to say whether the community would be behind it,” said Ms. McCarthy, who said she remains concerned that Unitil's aging electrical infrastructure in Lunenburg is vulnerable to continued outages. “I think they would deserve a real feasibility study to determine that. But I would say after what's happened, they would be open to it.”

Last week, in a parallel step, Lunenburg voters at a special town meeting unanimously passed a proposal to move forward with filing special legislation that would allow the town to acquire its own light plant.Even as legislative debate simmers, utilities and emergency officials are girding for another winter. The Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency is developing a database of equipment and assets around the state so it will have centralized information on material that can be deployed in an emergency, according to Peter W. Judge, a MEMA spokesman.

In Ashburnham, it cost about $860,000 to repair storm damage, according to Mr. Herriott. The municipal utility replenished its supplies after the storm and, over the summer, stocked up on an additional $12,000 in wires, brackets, fuses and other emergency materials.

National Grid, based in Waltham, changed its emergency and communications procedures, resource coordination and logistics, all as a result of lessons learned last year, according to Robert A. Kearns, National Grid director of emergency planning.

The company had previously stored repair kits in central locations for workers, he said, but will now move those kits out ahead of storms to locations where the company anticipates they'll be needed. Among other changes, National Grid is standardizing prevention checklists across all regions and has revamped its storm outage Web page and added capacity to its call center.

“We're going to have everyone operating under the same plans, same training, and we'll be able to seamlessly transition resources from unimpacted areas to impacted areas on a moment's notice,” Mr. Kearns said.

Contact Lisa Eckelbecker by e-mail at leckelbecker@telegram.com