Electric Costs May Go Up in Connecticut, but Not for All

George Ruhe for The New York Times

George E. Leary is in charge of a public utility that maintains a centuries-old cemetery in Norwalk.

By ALISON LEIGH COWAN

Published: December 4, 2006

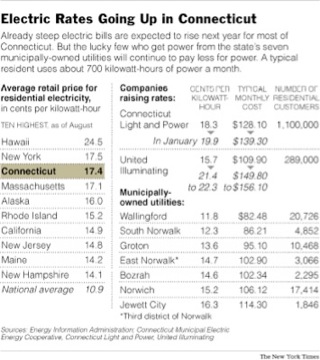

NORWALK, Conn., Dec. 3 — Monthly electric bills for Connecticut residents, already among the highest in the nation, are likely to jump again in January, with regulators poised to approve rate increases starting on Monday.

But not here in the eastern part of Norwalk, where George E. Leary runs what is known as the Third Taxing District’s Electric Department. His 3,800 residential customers will see no price increase in January and will continue to pay less — far less — for the same power that lights up much of Connecticut.

That feat is making Mr. Leary’s 93-year-old, municipally owned utility — and six other similar small entities across the state — look downright smart compared with the large, for-profit behemoths in his business.

“I think there are lessons there to be learned,” said Stephen J. Humes, a partner at the law firm McCarter & English who specializes in energy law.

Mr. Leary, who stepped into this job three years ago, has not only continued a Third Taxing District tradition of delivering power each year for less than what the giants charge, but has also ended each year with a surplus. “We make them look bad,” Mr. Leary said sheepishly.

Some of the surplus funds are plowed back into the business to ensure that the poles and lines remain in good condition. What is left after that — about $300,000 last year — goes into civic endeavors, like stocking the shelves of the East Norwalk Library, buying a new boiler for the firehouse on Van Zant Street and maintaining a centuries-old cemetery on East Avenue.

That cemetery is home to Thomas Fitch, governor of Connecticut from 1754 to 1766, and his son, Col. Thomas Fitch, the soldier whose ragtag troops stuck chicken feathers in their caps as a way to spot one another in the absence of uniforms. Their scrappy appearance popularized the song, “Yankee Doodle,” according to the tale inscribed on a headstone and a memorial.

Customers of the taxing district pay roughly 14.7 cents per kilowatt-hour. Connecticut Light and Power charges its 1.1 million customers 18.3 cents and has asked state regulators to let it set the price at 19.9 cents, an 8.3 percent increase. United Illuminating, with 289,000 customers, charges 15.7 cents and is seeking permission to charge between 21.4 cents and 22.3 cents, a jump of 36 percent to 42 percent.

Roughly 6,200 customers get an even sweeter deal from another small municipal utility elsewhere in town: South Norwalk Electric Works charges 13.8 cents per kilowatt hour and knocks 10 percent off a bill if a customer pays within 10 days. South Norwalk also has no plans to raise prices.

If the rate increase is approved, a typical Third Taxing District customer will pay $36 to $53 a month less than the customers of the big utilities do. Large users would save even more.

For Frances Scarpone, who lives on a fixed income, being a customer of the taxing district means “your mind is more at ease.”

But such bargains are few and far between in a state with residential electric rates that are the third-highest in the country, and they are almost impossible to replicate in places that do not already own their own utility.

At 17.4 cents, Connecticut’s average electric rates are far above the national average of 10.9 cents. New York State has the second-highest rates, at 17.5 cents, and New Jersey the eighth-highest, at 14.8 cents. (Hawaii tops the charts at 24.5 cents.)

In Connecticut, a total of seven municipally owned utilities — the two in Norwalk, plus others in Bozrah, Jewett City, Wallingford, Groton and Norwich — serve just over 60,000 people, fewer than 1 out of 20 of the state’s 1.4 million households. All seven have lower rates than the corporate utilities, ranging from 11.8 cents per kilowatt hour in Wallingford to 16.3 cents in Jewett City.

Spokesmen for C.L. and P. and United Illuminating said in interviews that they did not know much about the municipal business models, and said that they should not be faulted for raising prices when they cannot control the price of the electricity they buy.

“We’re at the mercy of suppliers,” said Mitch Gross, a C. L. and P. spokesman. As part of a deregulation of the power industry a few years ago, the for-profit utilities were encouraged to shed generating facilities so they could focus on the transmission and distribution of energy.

Now that older energy contracts are expiring, the large utilities say they are merely asking to be reimbursed for what they will spend to buy power for the next six months. “We’re not making a penny off it,” said Stephen Bravar, a United Illuminating spokesman. “It’s a pass-through. That’s it.”

The state Department of Public Utility Control is expected to approve the rate increases this week. “The market is what the market is,” said Beryl Lyons, the department spokeswoman.

Rather than generating power, the corporate utilities and the municipally owned ones both buy it these days, often from the same suppliers. So how are the little guys able to do so much better by their customers than the giants?

Some in the industry point to the fact that municipal utilities, unlike their corporate brethren, can issue tax-exempt bonds and do not pay local property taxes. But Mr. Leary’s balance sheet has no debt or need to raise outside financing. And if taxes were levied on his business property, it would not exceed $150,000 a year, based on current assessments, adding less than half a penny per kilowatt-hour to customers’ bills.

Mr. Leary, who spent years running a municipal gas-and-electric utility in his hometown of Holyoke, Mass., before arriving in Connecticut, suggested that the answer may be simpler: having just one master to serve rather than having to balance the needs of customers and stockholders as publicly traded corporations must. “Our primary interest is the customers,” he said.

And, he said, regulated competitors have little incentive to work as hard at finding the best deals. Under the state’s regulation system, the utilities cannot mark up the price of the power they purchase. Instead, they make their profit on the cost of transmitting it and distributing it.

But Mr. Bravar of United Illuminating rejected Mr. Leary’s hypothesis. He said his company consulted with state government officials when it was choosing suppliers. Another clue lies in the homely brick building that houses the third-district’s offices and its 10 employees.

Mr. Leary earns $125,000 a year and has a company car, but makes his own photocopies. “I am my secretary,” he said. The top executives of C. L. and P. and United Illuminating, on the other hand, both earned more than $1 million in salary, bonus and perks last year.

Not surprisingly, Norwalk is exploring a proposal to start a municipally owned utility for the large swaths of the city that are not covered by the two existing ones.

But such proposals face significant hurdles. Just trying to obtain the poles and wires often requires eminent domain, a tool that can expose a town or city to years of costly litigation.

In California, for example, a proposal to extend the territory of a public utility in Sacramento to include another 70,000 homes in nearby Yolo County was on the ballot this fall.

Pacific Gas and Electric, the for-profit utility whose business was threatened, spent $11 million to defeat the proposal.