POWER PLAY: UTILITY COMPANIES PULL THE PLUG ON COMPETITION

October 23, 2011

By Scott Van Voorhis and John Wayne Ferguson

New England Center for Investigative Reporting

In the chaos that followed Tropical Storm Irene, tiny town-owned power companies across the Bay State emerged as big heroes, in some cases putting the lights back on in a matter of hours.

The giant utility companies, which provide electricity to the vast majority of the communities across the state, lumbered for up to a week to get the power back on despite their deep pockets and fat bottom lines.

That stark contrast has sparked a surge in interest by cities and towns to get into the electric power business. But before fed-up communities can do that, and join cities and towns like Concord, Taunton and Chicopee, the state legislature will have to pass a bill that’s died in every legislative session for almost a decade.

The bill would revamp an ancient and cumbersome law that, since the 1920’s, has prevented any additional towns and cities from starting their own local utilities. It’s been blocked, year after year, by a well-oiled utility industry lobbying machine.

“We have basically gotten the big stall,” said Paul Chernick, president of Arlington-based Resource Insight, a consulting firm that’s been pushing various bills since 2001 that would let communities set up their own municipal electric companies.

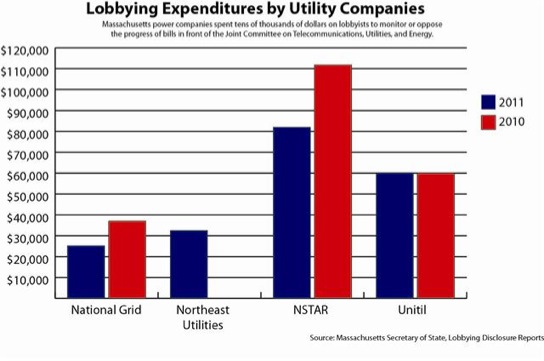

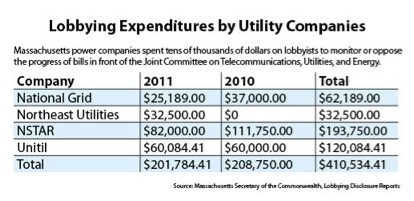

Over the past 18 months, NStar, National Grid and other investor-owned utilities have spent more than $400,000 on lobbying against that legislation and either for or against several other industry-related bills in front of the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilities and Energy, according to an investigation by the New England Center for Investigative Reporting (NECIR).

During the first six months of this year alone, the major power companies dumped nearly $200,000 on lobbying efforts to derail or influence the municipal power bill and weigh in on a range of other industry legislation, according to lobbying records at the Massachusetts Secretary of State’s Office.

NStar and National Grid were among the big spenders, state lobbying records show. Northeast Utilities spent tens of thousands of dollars on lobbying activity related to the municipal power bill and similar legislation this year alone, though it lists its position as neutral.

The money spent lobbying against a group of bills that includes the municipal power legislation accounts for more than half the $375,000 shelled out so far this year on Beacon Hill by power companies.

All told, the state’s major power companies have spent more than $4.6 million on State House lobbying since 2005.

“I had heard that the utility lobby is a potential force to be reckoned with,” said Fitchburg Mayor Lisa Wong said. “I would hope that wouldn’t be the case.”

Wong’s city has been trying to break free of Unitil Corp. since a devastating 2008 ice storm left some residents without power for weeks during brutal winter temperatures.

Backers of the municipal power legislation appear completely outgunned. Supporters, including the Massachusetts Municipal Association and the Massachusetts Alliance for Municipal Electric Choice, spent just a few thousand dollars on lobbying efforts in the first six months of the year.

The utility industry appears to be trying to influence decision-making on Beacon Hill, not only through lobbying, but also through campaign contributions.

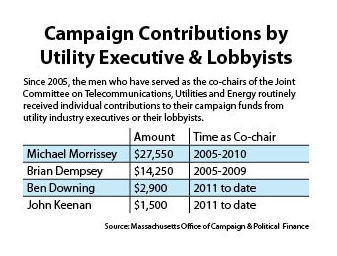

Over the past six years, five committee co-chairmen, along with other committee members and House and Senate leaders have reaped at least $55,000 in contributions from utility company executives and lobbyists, the NECIR investigation found.

Before taking leadership positions on the committee, the legislation in question drew little interest from the industry.

Sen. Ben Downing (D- Pittsfield) took over as Senate co-chair of the powerful Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilities and Energy at the start of 2011.

In the first six months of 2011, he has received more than $2,900 in campaign contributions from both power industry lobbyists and executives, state records show. The contributions stand out in a quiet, non-election year.

Downing’s response is that anyone is free to donate to his campaign, but those donations, he said, do not affect how he votes.

“If people want to donate to my campaign, that’s fine, but it’s not going to affect my position on this bill or any other bill,” he said.

His co-chair on the House side, Rep. John Keenan, (D-Salem), has also received roughly $1,500 in contributions from the industry since becoming co-chair at the start of the year. Like Downing, he had not previously enjoyed the largesse of the utility industry until assuming the co-chair post.

“We will make a decision based on the merits and that has nothing to do with who contributes,” Keenan said. “I raise $50,000 to $60,000 a year. To suggest my vote can be bought is ludicrous.”

Downing and Keenan are not alone. Past co-chairs of the committee, which oversees a range of legislation of interest to the utility industry, have also cleaned up when it comes to campaign contributions from utility industry executives and lobbyists.

Former State Sen. Michael Morrissey, now Norfolk Country District Attorney, who co-chaired the Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilities and Energy for most of the past decade, took in more than $27,000 from the industry from 2005 through 2009 alone, state records show.

Rep. Brian Dempsey, (D-Haverhill) who put in a co-chair stint from 2005 to 2009, pulled down more than $14,000, most of that coming during his years as co-chair, state records show. Now chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, Dempsey may again play a role if the bill advances. Dempsey said his decision not to move the muni bill forward had to do with concerns about the legislation itself. As for the campaign contributions, he said they total just a small percentage of what he raised overall.

For towns and cities seeking the freedom to ditch the mainstream power companies, the fate of the last major utility proposal debated on Beacon Hill last year may be instructive.

Morrissey, the Senate co-chair, reported the bill out of committee on June 23, 2010, just a little over a month before the legislative session was set to adjourn.

And the bill, before it was released, was also rewritten in a way that would effectively make it hard, if not impossible, for most cities and towns to afford to buy out their local electric lines and poles from one of the big utilities, Kaufman contends.

Morrissey brushed aside questions on contributions made to his campaign during the years he co-chaired the Joint Committee on Telecommunications.

He noted contributions from lobbyists – which account for part of his haul from the utility industry – can be hard to attribute to any particular issue. He said lobbyists typically have multiple clients spanning industries; someone lobbying for a utility company may have also been hired by a casino operator as well. Morrissey also noted he has sometimes voted against the industry, passing legislation that enabled cities and towns to take control of their street lights.

But he contends backers of town-owned power plants have simply failed to make a similarly compelling case on why the 1920s-era legislation should be changed.

“No one has fully articulated what is wrong with the existing statute,” he said.

Most of the 41 communities in the power business got their start in the 1920s when they were small rural hamlets bypassed by utility companies rolling out their electric grids.

But the rules that allowed communities to set up power businesses almost a century ago no longer work today. They effectively give utility companies veto power over any community seeking to go it alone, critics say. And these days the big power companies have no interest in losing major cities and towns as customers.

“We value all of our customers and wouldn’t want to lose any of them for any reason,” stated Michael Durand, an NStar spokesman, in an email.

The result has been a decade of dead-on-arrival proposals to give more leeway to communities interested in getting into the power business. Backers more often than not have been unable to even wrangle a meeting with legislators to make their case.

“To have not gotten serious attention over three years, let alone ten years, that is a little discouraging for democracy,” said Chernick.

Still, backers of long-stalled legislation are hoping this may finally be the year after a decade of thwarted hopes.

Outrage over Irene is still fresh and both state regulators and State Attorney General Martha Coakley has launched reviews of how the big utilities behaved during the gale.

“Irene is the latest witness to the importance of passing this bill,” said Rep. Jay Kaufman, (D-Lexington), who has been the chief legislative sponsor of the bill making it easier for cities and towns to go into the power business.

While Chernick said he was encouraged by a rare sit down a few weeks ago with the co-chairs of the Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilities and Energy, it was just the third such meeting he had in decade.

“It is absolutely critical to get face time to make your case,” said Pam Wilmot, executive director of Common Cause Massachusetts, an nonprofit pushing for tougher campaign finance and lobbying laws.

Meanwhile, the major power companies object to the proposed legislation, arguing it would not set a fair purchase price for the local electric lines, poles and other equipment they would be required to sell.

“And, like any company, our equipment costs are recovered through our rates. So if a town is looking to take over that equipment, it’s only right that we’re able to insist on a fair price for it,” said NStar’s spokesman.

Both NStar and National Grid say lobbying and contribution records attest to nothing more than participation in the political process.

“Providing support to individuals running for office is a well-established part of the political process, just as lobbying is a well-established way to share one’s views on issues coming before the legislature,” Durand wrote. “We intend to continue to participate in both whenever we feel doing so is important to our customers and our company.”

In addition, National Grid, while declining to provide a figure, noted that its own lobbying expenditures on the bill were far below the hundreds of thousands spent by the industry as a whole, according to spokeswoman Debbie Drew.

No matter how much utility companies spend to try to get their way on Beacon Hill, many cities and towns are hoping that a backlash against the state’s major power companies will finally carry the day.

The New England Center for Investigative Reporting (www.necir-bu.org) is a nonprofit investigative reporting newsroom based at Boston University.